Revisiting the History of the Finnish Tolstoians

Rony Ojajärvi

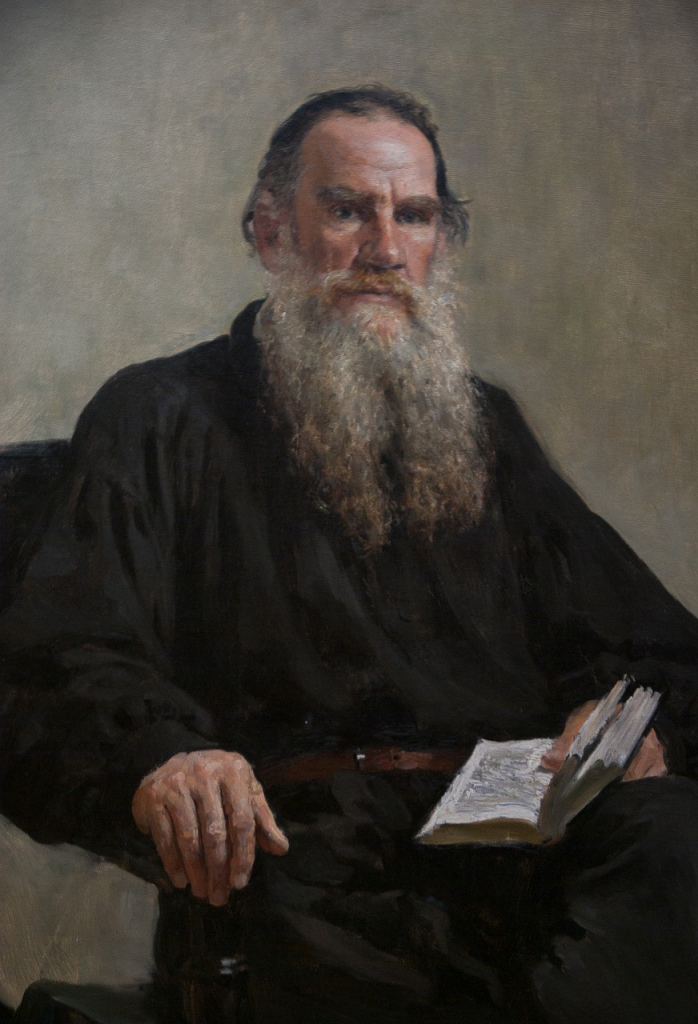

Finland, due to its long history and shared border with Russia, has been influenced by the religious traditions that developed in the soil of our eastern neighbour. The Tolstoian tradition is historically interesting in this sense. Leo Tolstoy, after fighting in the Russian army, made an about-turn and became a strong advocate of non-violence. After he published a series of novels – most famously Anna Karenina and War and Peace – as well as numerous political and religious pamphlets, his ideas began to spread quickly across Russian borders. Around the turn of the 20th Century, he began to gain his own followers, who became known as the Tolstoians.

Tolstoy’s theological interpretations support the political engagement by religious people. Tolstoyism has, in different research studies, been defined most often as a Christian anarchist, religious-political tradition. Tolstoy viewed churches and state institutional structures very critically. He took the teachings of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount very strictly and based most of his theology on them. This was also the reason that Tolstoians were radical pacifists who aimed to give up all their property in order to live self-sufficiently in the countryside.

Tolstoian teaching influenced a variety of different social activities and movements that developed as industrialisation and urbanisation enabled and produced new kinds of social communities. Examples of this are the movements developed around ideologies such as anarchism, socialism, communism, communitarianism, vegetarianism, temperance, pacifism and theosophy; In all these ideologies, Tolstoy has been regarded as an authority figure.

A transnational perspective

Different Tolstoy-inspired political movements in diverse national and international contexts have recently been under scrutiny. In the context of Finland, Armo Nokkala wrote his doctoral thesis, Tolstoilaisuus Suomessa – aatehistoriallinen tutkimus [Tolstoyism in Finland – Research on the History of Ideas] in 1958. Using traditional influence analysis, where one traces “the chain of influences” between different thinkers, Nokkala analyses a variety of Finnish thinkers and movements in relation to Tolstoy’s teachings. The shared history and border with Russia enabled Tolstoy to become influential in Finland. The most well-known Tolstoian was Arvid Järnefelt, a Finnish writer, who kept in contact with Tolstoy and referred to his ideas in his novels and other writings. In his research, Nokkala also documented the ways in which the Finnish working-class movement and theosophists, like Yrjö Sirola, Pekka Ervast and Matti Kurikka, all depended on Tolstoian teachings, especially in their critiques of the Church.

After the publication of Nokkala’s thesis, research regarding the history of the Tolstoians took a step forward. The rising popularity of transnational history research in particular has given rise to interesting areas of focus in the research field. Lately, Irina Gordeeva, a historian, has surveyed the transnational spread of the Tolstoian tradition from Russia to other parts of Eastern Europe and around the globe. An important contribution she has made has been to survey the huge archive (about 65 000 pages) of Vladimir Chertkov, a close friend of Tolstoy and leader of the Russian Tolstoian movement. The Chertkov archive in Russia was closed for a long time, but the opening of the archives around 2010 enabled Gordeeva to deepen the knowledge of the academic community about the Russian roots of transnational Tolstoians.

Gordeeva has shown how Vladimir Chertkov, as well as Valentin Bulgakov, Tolstoy’s last secretary, networked intensively with international peace movements, most importantly the International Fellowship of Reconciliation and War Resisters’ International, which were constituted after the First World War.

Tolstoian-inspired ecumenical humanitarian aid

It is particularly through the International Fellowship of Reconciliation that new, previously unexplored research themes arise in the religious history of Finland. The most important Tolstoian in the history of the Finnish branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation was Oscar von Schoultz, a lecturer of Russian language at the University of Helsinki. Armo Nokkala surveyed Schoultz’s biographical history in his PhD. Schoultz participated in the Russian military in the latter half of the 19th Century but resigned from the army after becoming acquainted with the teachings of Tolstoy. According to Nokkala, Schoultz ended up owning the biggest Tolstoy library in Finland. But what is not covered by Nokkala is Schoultz’s ecumenical and transnational – and even translocal – co-operation through the International Fellowship of Reconciliation in the 1920s.

After the 1917 Russian revolution, thousands of refugees poured across the border from Russia into Finland. It was a humanitarian crisis. The Russian refugees were in poor health and the unemployment rate was high. Many Russians had heard that Oscar von Schoultz had been active in Finland in fundraising for the victims of the Armenian genocide, a fundraising project initiated by the Swedish branch of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation in 1921. Russian refugees sent Schoultz a letter asking for help, which he shared with the members of the Finnish Fellowship of Reconciliation, including Mathilda Wrede, a Finnish woman evangelist. Under the leadership of Schoultz and Wrede, the Finnish Fellowship began to allocate funds, clothes, food and work to refugees living in Finnish towns close to the Russian border.

This humanitarian aid project for Russian refugees improved transnational relations, at least between Russians, Ukrainians, Serbians, Swedes and Finns. For example, the Finnish Fellowship of Reconciliation, and particularly Oscar von Schoultz, actively co-operated with Vladimir Tukalevsky, a Russian-Czech historian, who lived in Terijoki and organised relief work and reported the results to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation. His reports, as well as the more specific documentation on the humanitarian aid project among Russian refugees, is available in the archives of Mathilda Wrede in Svenska litteratursällskapet (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland) (SLSA 859, 2.2.). The humanitarian project was also ecumenically enriching, as Tolstoian, Lutheran, Catholic and Orthodox Christians worked together actively in order to help refugees. For example, one crucial provider of help in Terijoki was the first Finnish Catholic priest to be ordained after the Reformation, Monseigneur Adolf Carling. On Christmas Day in 1923, he distributed food, along with the local Orthodox priest, which was reported on with great joy by Vladimir Tukalevsky. Hopefully these parts of the transnational and ecumenical history involving Finnish Tolstoians will someday be studied.

Rony Ojajärvi ([email protected]) is an Early-Stage Researcher at the University of Eastern Finland. He is currently doing his PhD in the field of Church history on the topic “From Christianity to Atheism via Religious Syncretism? The Religious Variable in the History of Finnish Peace Movements 1919–1975”.