Exploring the Central Cemetery of Grenoble

Established by the blessing of the bishop of Grenoble Claude Simon on August 19, 1810, Saint-Roch Cemetery (Cimetière Saint-Roch) is the largest cemetery of Grenoble. It exists inside a curve of the river Isère, quite close to the city center but has some calming park zones around it. Already in 1497 on this site there was a plague hospital and a cemetery. Saint Roch Cemetery’s own website calls the place “an open-air museum”, which is often ignored by locals. While the description is correct about the place’s museum feeling, there are also some recent graves, so the museum characterization seems a bit odd to me. Yet, as a person who is usually barely interested in architecture, I was amazed by this cemetery. As usual with cemeteries, it was challenging to put the experience into words, so this blog post relies much on images.

The cemetery feels massive, not so much by its area, but due to its structures. Dense big spruce trees together with the setting sun make few of its corridors feel quite gloomy. The gravestones are astonishingly large and many of them make walls so tall that I cannot see past them. Some of them come across to me like grim castles.

Notably many of the graves here, as in smaller graveyards that I have visited on the outskirts of the city, are family graves. For me as a Finnish outsider, this observation gives the impression that belonging to families is highlighted more here than in Finland. On the other hand, the monumentality of the gravestones implies that these families are particularly wealthy. Indeed, Grenoble’s other cemeteries further from the city center where I visited did not have so many graves of this stature.

Similarly, as in Barraux, there are several individual signs on the graves, from images of the deceased to messages from their bereaved. For this cemetery walk, I was accompanied by my wife who could translate some of the messages, which enhances the feeling of their intimacy, the feeling that these were once people, who now keep on living in memories. For a moment, this makes me think about the ephemerality of my life. Then the question comes to my mind – how much do the people leaving these messages think about bypassers as readers of these messages?

The French national identity is signaled right at the entrance of the graveyard, which is covered with the French tricolor flags (image 1) and then again, in the military grave site, which perhaps surprisingly does not have the most central location of the cemetery. Instead, at the end of the main boulevard corridor leads to the 1826 established chapel of Saint Roch (image 2 and Image 5). On the other hand, right next to the chapel stands a monument dedicated to the fatalities of the Franco-Prussian war (1870–1871), which was sculpted by Eustache Bernard in 1893 (image 8).

Generally, in many countries’ public commemoration, the most prominent element is the war memorials. While WWII is more recent, and perhaps narratively more outstanding in public memories of many countries, Finland included, in this deathscape WWI appears to be arguably even more prominent as many more soldier graves are dating to 1914 to 1918. This is no wonder since there were overall approximately 1,9 million French fatalities from the conflict – over three times more than in the Second World War. However, I need to point out here that I found a few different numbers via Google searches and it was often unclear whether colonial troops were counted in this number. November 11, the Armistice Day of WWI is also (still) celebrated as a public holiday in France, but unfortunately, I got little perspective of how the French celebrate this day.

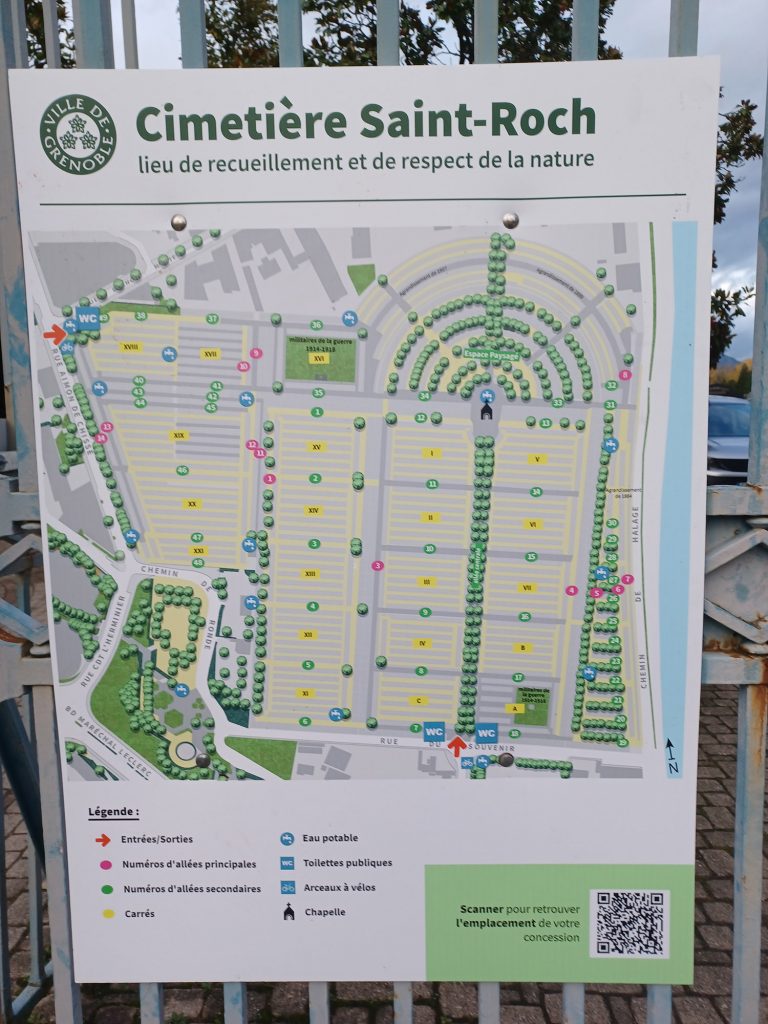

Among the crosses dominating the WWI grave site, there were a couple graves of Muslims, and many more of them located in the last and second to last rows (from the point of view of entrance and the texts). I guess these were France’s colonial troops, and while I do not know about the reasons for their location on the last rows, they did not seem to stand equally from the point of view of an illiterate outsider such as me. Additionally, I later read from Wikipedia that also American and Italian soldiers were buried on this site. I also missed a memorial for German soldiers from WWI and a pre-WWI soldier burial site on the edge of Saint-Roch, which apparently was not very prominent, because according to the map I walked past it.

With all respect to the locals, the bereaved, and the dead, I could not help but think about the redundancy of these war fatalities, which got me in a foul mood thinking about the ongoing wars going on in the world.

As a side note, there were several memorials around Grenoble, among others a memorial for the victims of the Gestapo in the village on the hill of Le Mûrier, a common memorial for the fatalities of WWI, WWII, and the Algerian War (1954–1962) in front of a school and even a French Revolution (1789) memorial on the Square of Liberty. There is also a Museum of the Resistance and Deportation of Isère (the province) because it was closed at the time when I tried to get in.

For further exploration of the French (trans-)national memory, it would be interesting to find more about the commemoration of the Algerian War, as many of its eye-witnesses are still alive, the pre-independence status of Algeria was officially not a colony but a part of the motherland, and the Algerian minority have a long and complicated history in France.

Image 9: Memorial on Le Mûrier dedicated to the victims of Gestapo during the Nazi occupation and after return from the camps.

During our nearly 45-minute walk, we noticed a few names that didn’t appear French. Most of them resembled Italian and Polish names, though it’s possible that we missed many. Notably different national and religious symbols were difficult to spot.

Our walk suddenly came to an end when a graveyard keeper approached us riding a bicycle. He told us that it was time to leave as the cemetery was closed. The timing was not bad, considering the diminishing light that made it difficult to read the grave inscriptions from a respectable distance. We headed towards the entrance/exit gates and waited with another visitor. The cemetery keeper completed his round, ensuring no one was still wandering in this large cemetery after closing time. Hopefully, he found everybody; it would be quite a scary place to be locked up for the night, no matter how interesting.

Teemu Oivo

Postdoctoral Researcher

Karelian Institute, University of Eastern Finland

To read other blogs from the Transnational Death project, click here, here or here.