Researching Territorial Identifications Using Mental Maps

How do young people understand and represent Finland’s borderline and the Finnish-Russian borderlands

Väitöskirjantekijät Chloe Wells ja Virpi Kaisto kirjoittivat yhdessä artikkelin mielikuvakarttametodista Journal of Borderlands Studies-lehteen. Idea yhteisestä artikkelista syntyi, kun he huomasivat molemmat tutkineensa nuoria ja käyttäneensä mielikuvakarttametodia tutkimusmenetelmänään. Chloe tutki menetelmällä suomalaisten lukiolaisten suhdetta Suomen toisen maailmansodan jälkeisiin rajamuutoksiin, ja Virpi Suomen ja Venäjän raja-alueella asuvien suomalaisten ja venäläisten nuorten mielikuvia rajasta ja raja-alueesta. Yhteisen artikkelin tavoitteena oli pohtia menetelmän soveltuvuutta nuorten alueellisten identifioitumisprosessien tutkimiseen, ja nimenomaan siihen, millainen merkitys rajoilla ja rajanvedoilla (bordering) on näissä prosesseissa. Artikkelissa todetaan, että mielikuvakarttamenetelmä sopii hyvin nuorten alueellisten identifioitumisprosessien tutkimiseen eri aluetasoilla. Valittu metodologia kuitenkin määrittää sen, mitä rajoihin ja rajanvetoihin liittyviä ulottuvuuksia voidaan saada selville ja miten syvällisesti alueellista samaistumista voidaan tutkia mielikuvakartoilla.

When discussing our PhD projects roughly two years ago, we realized that we were both doing research with young people and had both been using the same method of data collection – that of mental mapping. Chloe’s PhD focuses on the Finnish postmemory of the city of Vyborg (Russia), and she had collected mental maps from Finnish high school students (aged 16–19) to discover how they relate to Finland’s borders and territorial shape, and how they understand and represent the changes to Finland’s borders which occurred as a result of World War II (WWII). Virpi studies the Finnish-Russian borderland in her PhD, and she had used the mental mapping method to study Finnish and Russian young people’s (aged 9–15) perceptions of the Finnish-Russian border and borderland, in collaboration with Olga Brednikova of the Centre for Independent Social Research, St. Petersburg. Our mental mapping approaches differed from one another, and we decided that it would be beneficial to compare our methodologies and to engage in writing a joint paper.

Our fruitful collaboration began with a joint presentation given at the BoMoCult/CultChange Conference held at UEF in October 2018. After this we worked on an article for publication in the Journal of Borderlands Studies. Our article, ‘Mental mapping as a method for studying borders and bordering in young people’s territorial identifications’ was published online by the journal in February this year.

The main questions which motivated us, as Human Geographers, were: How are borders and territorial identifications intertwined in young people’s spatial imaginations? How do young people engage in the social, cultural and mental construction of borders and the negotiation of territorial identities? How to use the mental mapping method to investigate these questions?

In the article, we state that identity processes related to borders have been well studied among adults, whilst the study of borders in young people’s territorial identification processes is only beginning to develop. Our aim was to contribute to filling this knowledge gap, because we believe that studying young people’s engagement with borders and their social, cultural and mental construction of borders (‘bordering’) has the potential to enrich the understanding of borders in general.

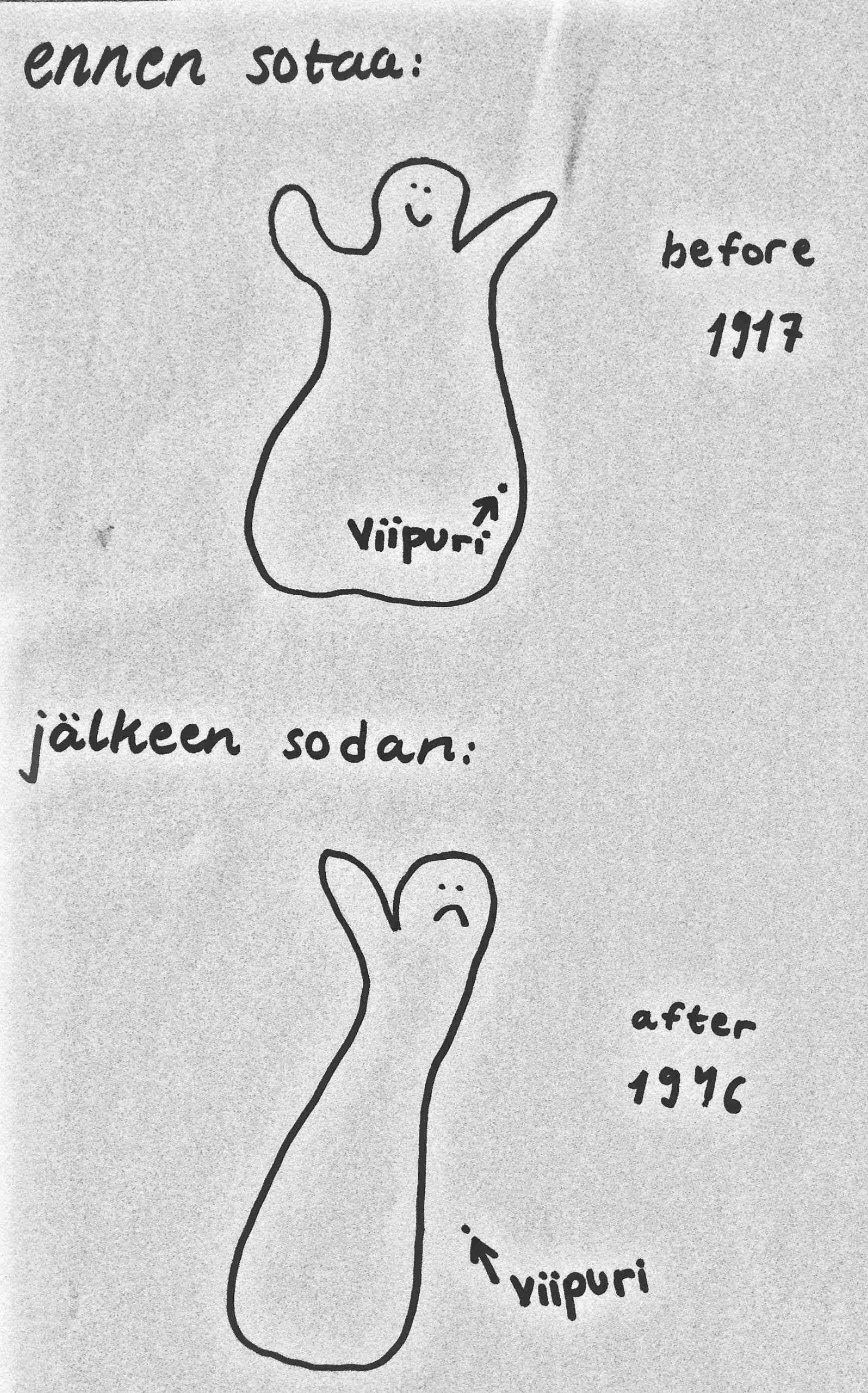

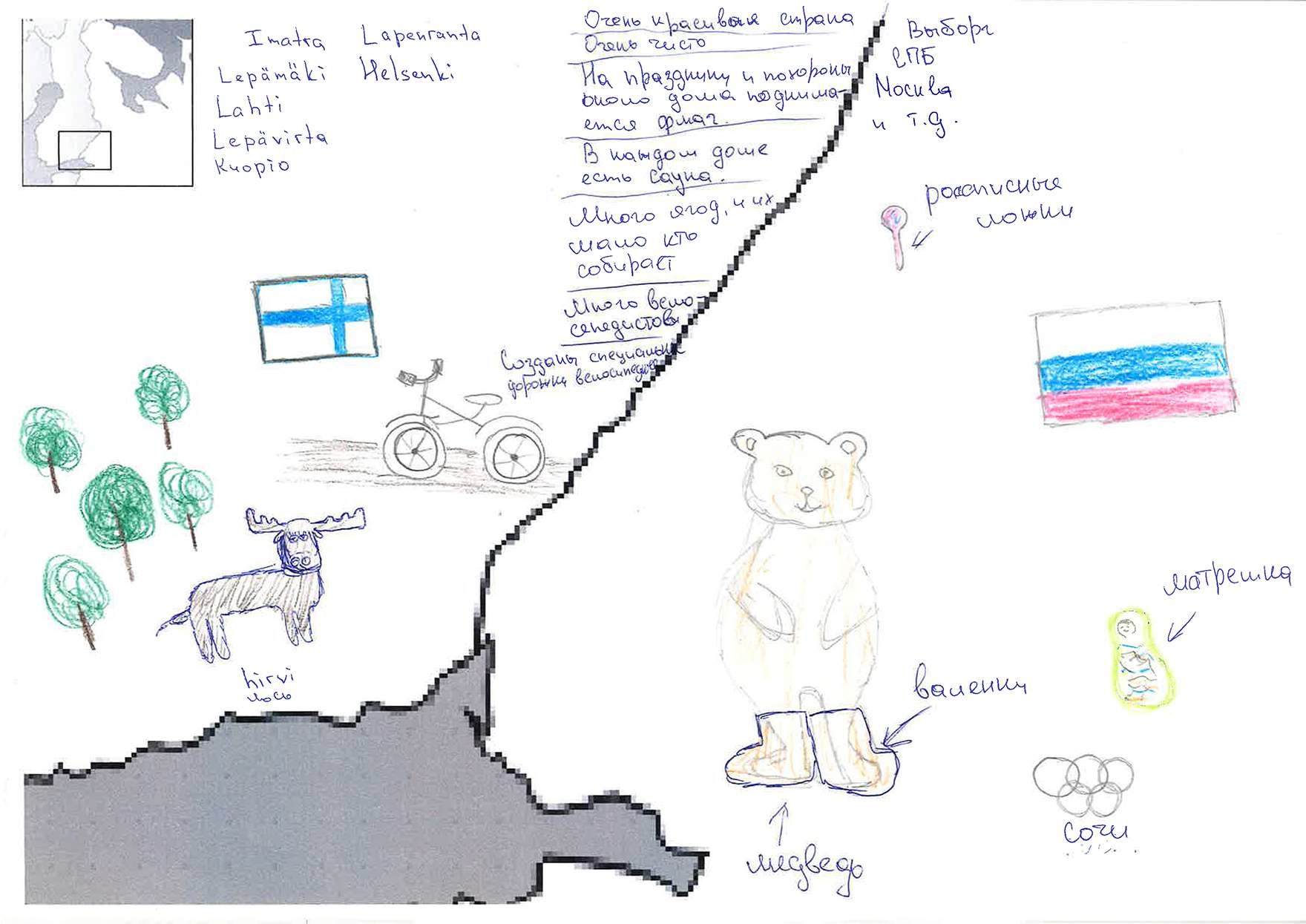

In our studies, mental mapping proved a suitable method to examine borders in young people’s territorial identification processes. Mental maps reflect both individual and collective world-views, and mental mapping can be used as a standalone method or combined with other methods which provide more explanatory power. In Chloe’s study, participants drew on a blank piece of paper two outline maps of Finland, one ‘before WWII’ and one ‘after’ (see fig. 2). The maps were an ‘ice breaker’ exercise for focus group discussions and, thus, could be supplemented with focus group transcripts and feedback forms collected after the focus groups. Virpi got participants to add drawings and text to a base map showing the south-east section of the Finnish-Russian border and borderland (see fig. 1). The maps served as the only research data.

Chloe’s study provided insight into the role and significance of a nation’s borders and shape in young people’s territorial identifications. It showed how young people perceive ‘Finland’ as an outlined territorial entity and relate to the changes to its borders and ‘geo-body’. The study also illustrated how the mental mapping method worked in combination with other methods. Virpi’s study foregrounded borderlands as central sites for exploring processes of bordering and the construction of national and other collective identities. Her study illustrates the possibilities and limitations that mental mapping as a standalone method has for examining territorial identifications in borderlands.

Our collaboration and the comparison of our two studies highlighted how the mental mapping method can be fruitfully used to study territorial identifications at different scales, and as part of different methodologies. We also showed in our article however, how the research methodology, including the mapping scale and the complementary data collection methods, determine what aspects of borders and bordering in young people’s territorial identifications can be discovered, and how profoundly identification processes can be studied with mental maps. Combining quantitative and qualitative analysis techniques in both studies led to an understanding that the young people had both socially shared and individual ways of relating to and mapping national borders and borderlands.

Kaisto, V. and Wells, C. (2020) ‘Mental Mapping as a Method for Studying Borders and Bordering in Young People’s Territorial Identifications’, Journal of Borderlands Studies. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2020.1719864

Other references:

Kaisto, V. and Brednikova, O. (2019) ‘Lakes, presidents and shopping on mental maps: children’s perceptions of the Finnish – Russian border and the borderland’, Fennia, 197 (1), pp. 58–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.11143/fennia.73208

Kaisto, V. and Wells C., (2018) ‘The mental mapping method and the spatial socialization of young people’, paper given at the 5th Annual BoMoCult /CultChange Conference, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland, 4-5 October 2018.

Authors

Chloe Wells

Early Stage Researcher

Department of Geographical and Historical Studies

Virpi Kaisto

PhD Researcher

Karelian Institute