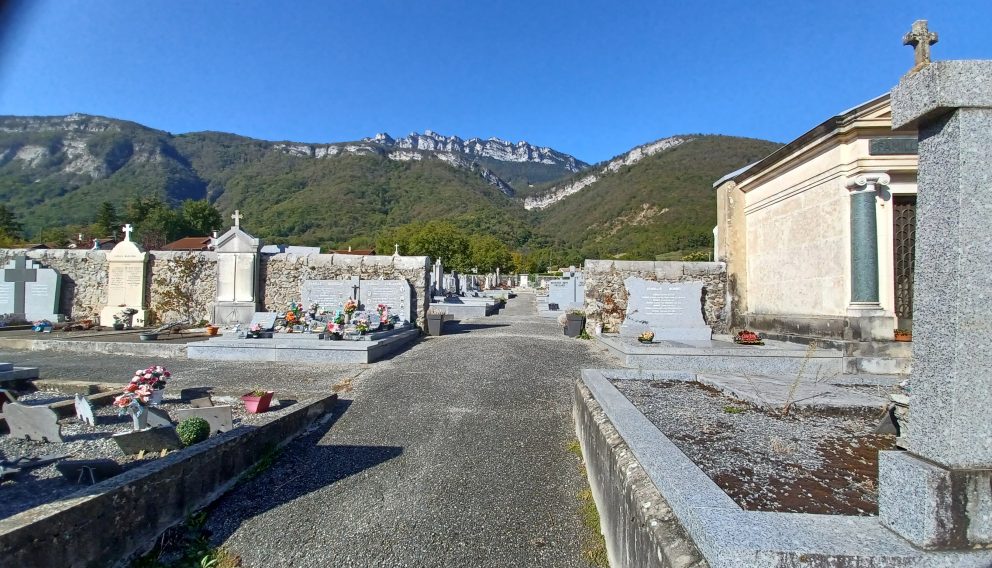

Grenoble cemetery

Greetings from France!

I am here at the root of the French side of the Alps doing a research exchange in Grenoble from October and November 2023 as part of the Academy of Finland-funded project “Transnational Death”. The plan is to give a couple of lectures, one research seminar, and network at the Université Grenoble Alpes, as well as conduct some light drifting ethnography on cemeteries here. This “drifting” continues the approach widely applied in our project, where we give added value to drifting ethnography through the wondering “wrong gaze” of an individual living transnational everyday life. It seeks to describe the way this individual observes, experiences, and understands cemeteries, which are typically constructed in national contexts around the universal death and as places that affectively combine public and private spaces. Mattias Frihammar and Helaine Silverman (2018, p.8) have described the meaningfulness of cemeteries as follows:

“Cemeteries, of course, by definition, are landscapes of death. But they are first and foremost territories that knit together the individual and communal dimensions of death and implicate cultural, political, ideological, religious and economic decisions about the creation of physical space for them. They also implicate the social construction of space and societal conceptions about the place of death in society. It is at the cemetery that notions of person, family, kinship and nation get physically interwoven.”

While I had previously adjusted my eyes onto this gaze in Finland (Hautausmaat ylirajaisuuden tiloina Idäntutkimus 3/2022) now, in France, it was natural for me to take a look with a stranger’s eyes. The first cemetery I visited was “Allée du Souvenir Francais” (French Memory Alley) in the mountain village Barraux, approximately 40 kilometers north of Grenoble. I narrated my experiences to my phone’s recorder in the cemeteries and immediately after exiting them.

View to the gate of cemetery Allée du Souvenir Francais

I barely found the cemetery in the first place, because while I saw a recognizable direction sign ”CIMETIÈRE” in the center of Barraux, it wasn’t marked on Google Maps and I ended up on a wrong road. This was a good reminder of the value of the traditional offline orientation skills. Google search found nothing about this place. Fortunately, I spotted a low brick fence and crosses behind a field, correctly guessing them to sign the cemetery.

The cemetery is located right on the edge of the village of Barraux and walking on its corridors the noises of children playing right next to the cemetery are easily heard. In other directions it is surrounded by fields, forest, and mountains. The landscape around the cemetery distracts me a bit regardless of the intrigue of this rather small cemetery. The locals probably would not be equally distracted as a person like me who is not used to mountains.

It is difficult to describe the excitement and certain level of discomfort in words when entering the gates of the first French cemetery. It is strange.

I immediately note how there seems to be lots of stone and marble. The tombstones are large and cut in various different forms and the ground ahead of them is covered with stone plates with smaller engraved plates on them. Besides the brief engraved messages (which are behind my language barrier), some of the plates depict the hobbies and lifestyles of the deceased, including many hunters with their shotguns and hunting dogs. The images of hunters get associated with sounds of shots and dogs barking from the hills, continuing the lifestyle that others left behind, but are still commemorated here. Some images seemingly depict professions of the deceased. Additionally, there are a few military and war symbols, probably close to the same amount as that I have grown accustomed to in Finnish cemeteries.

Only a couple of tombs are seemingly unmaintained, reflecting perhaps that the people have by and large stayed in the surrounding villages. At least the attendees of the local harvest festival suggested that there are a lot of families with children here. Among the names on the tombs, there are not many non-French associating names. I mostly associate them with Italian, but also occasional southern or western Slavic style names. During my drifting on the cemetery corridors, I did not notice other symbols indicating cultural variety.

There are bushes, but no trees in this cemetery. The omnipresent stone material sits well with the backdrop of the mountains that lie in every direction. In my mind, these stones imply an older age of this cemetery than what it probably is, considering that there are only a few tombstones dating back further than the twentieth century. Emotionally overwhelmed as I was on my ‘drifting’ walk, I forgot to memorise the oldest dates.

This feeling of the cemetery’s old age makes me feel like it is more universal than exclusive because I feel that things of the distant past do not separate me from my contemporaries with whom I can at least share the presence. In other words, the cultural and national dividing lines of the past centuries feel to me much less relevant than what I may encounter today (albeit the locals here have been welcoming and nice to me). Of course, the cultural perspective of my gaze is arguably not particularly distant from the people who made this cemetery and what might be expected from a default French visitor to the cemetery. Despite the language barrier, Christianity (and perhaps Europeanness) is prominent neutral in this cemetery as in cemeteries that I have become accustomed to in Finland.