A summary of the 4th edition of the International Possibility Studies Conference

Between 8th July and 12th July 2024, the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge hosted the 4th International Possibilities Conference. As the name of the conference denotes, fostering possibility thinking in the mind, communities and cultures was the central theme.

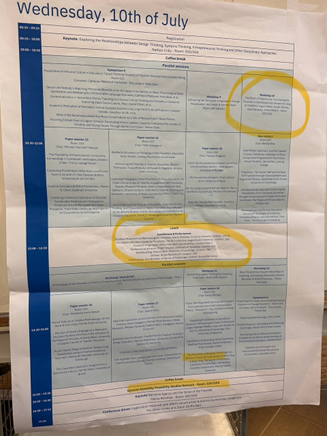

Keynotes opened and closed each of the five conference days. Throughout the day, the delegates had to make tough choices about which of the many parallel and interesting paper presentations and workshops they would attend.

Since creativity is the research area of interest for myself, I will present some of the fascinating ideas that revolve around this multifaceted concept. As a disclaimer, for the sake of brevity, I will not provide a comprehensive summary of all the inspiring presentations.

Monday, 8th of July

The conference was opened by the keynote, “The Power of Education for the 21st Century”, by Lord Simon Woolley, Principal of Homerton College in Cambridge. Two messages stroke a chord in me:

1) have a dream about positive social change, make a plan and take action;

2) adopt a leadership style based on directly experiencing how your subordinates’ workdays flow. This boils down to regularly spending some hours doing the work that your people do, side by side with them. For instance, to spend time with the cleaning personnel, get down to your knees and start scrubbing the floor.

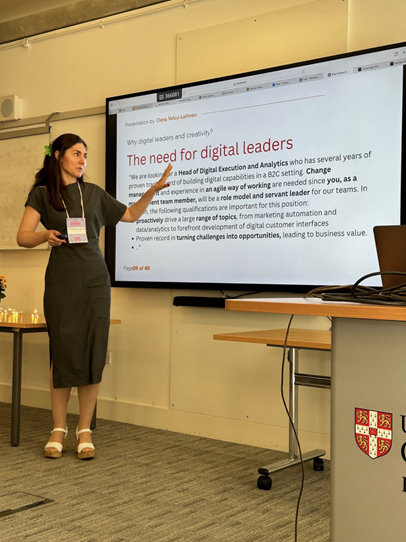

The keynote was followed by a coffee break, and right after it, my presentation followed, scheduled for the paper session 1.

Entitled “Exploring the Role of Creative Self-Concept of Digital Leaders for Effective Leadership during Digital Transformations”, the paper fits in the organizational behavior and leadership development field. It aims at understanding in what ways the creative self-image of leaders influences their leadership styles when faced with challenges during digitalization. I thus discussed the following key issues:

- Why digital transformations are a useful phenomenon for studying leaders’ creativity beliefs.

- What aspect of creativity is on focus.

- Preliminary findings based on the interviews collected at the time of the conference.

Why are digital transformations a useful phenomenon for studying leaders’ creativity beliefs?

In my research, digital transformations are defined as organizational initiatives to build digital capabilities through the integration of traditional information systems and emerging digital technologies, such as AI, IoT, mobile apps, etc, and to derive business value. Companies see digital transformations as solutions to a VUCA world, where decisions must be made in an environment is characterized by:

- volatility – each day can bring unexpected challenges for an unknown period;

- uncertainty – inability to predict the future based on past events;

- complexity – problems have many interconnected variables and it can be overwhelming to process the available information;

- ambiguity- making decisions without knowing how they will affect others.

Through digitalization, companies can collect more relevant and up-to-date information for decision-making. Still, it’s up to leaders and experts to interpret the information and share it. And that’s where creative actions can make a difference.

What aspect of creativity is under investigation?

In general, creativity studies that investigated the relationship between leadership and creativity, considered the latter construct as an outcome, as new and useful ideas, behaviors or products to improve the functioning of an organization.

In the presentation, I use the term “creativity” to refer to the creative self-image, the extent to which leaders value their creative thinking and see it central in their professional role.

Preliminary findings based on the interviews collected at the time of the conference

If I am a creative leader, in what ways am I creative?

Based on the interviews I succeeded in taking by the beginning of July, some leaders interviewed seem to value their creativity, which they understand as a practical way of thinking and solving conflicts at work. In addition, they are aware that they are not equipped with artistic creativity. Rather, they realize that their creativity requires a trigger —situations that are characterized by novelty or higher levels of challenge. Yet, they may not always recognize the situations when they use their creative qualities, such as curiosity, imagination and intuition.

What does it take for some leaders to become role models of creative leadership?

To become a role model in creativity and achievement, in addition to showing originality and unconventionality in their actions, they must show morality and at the same time, display similar values with the possible followers.

What are the most evidenced leadership styles?

“I would say, younger in the career, you try to be the, basically to be the leader, out of the books.”, a leader commented. “I think the further you age and the further you grow, the more you embrace your own style. You don’t need to hide things because you want to be someone you are not. You can be basically, you can have your own style and quite often, the more you have your own style, the more you are authentic.”

In addition to authentic leadership, leaders described their way of leading as empowerment leadership, servant leadership, and participative leadership, which reflect their values in the relationships with the followers. By contrast, creative leadership, also known as leading with creativity, is a leadership style discussed in academia, which reflects the how of behaving in new situations with team members. The creative leadership behaviors weren’t recognized by the interviewed leaders as a specific leadership style.

What’s seems to be the association between creative self-image and leadership style?

Not strongly identifying oneself as a creative individual seems to be associated with less communication and exchange of feedback with team members. By comparison, leaders who see themselves as creative individuals are more likely to be engaged in creating the company vision, creating new business themes and being involved in mitigating conflicts.

Overall, these preliminary findings suggest that new challenges trigger creative leadership behaviors, some of which leaders are conscious of. These results have important implications for team leadership under organizational change.

In the same session as my presentation, three other research projects were presented, as follows:

- Armina Popeanu, affiliated with “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urban Planning Bucharest, presented the aBC method for business modelling, crafted for creative entrepreneurs who are driven more by their creative ideas and may benefit from business thinking in leveraging their artistic talents on the market.

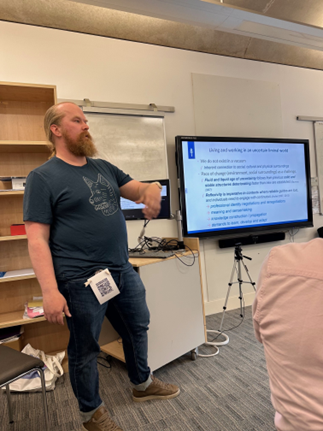

- Joel Schmidt and Min Tang, representing the Institute for Creativity and Innovation, University of Applied Management | Hochschule Schaffhausen, tackled the theme of work and people management in organizations by discussing the necessary skills and competencies for employees in a future characterized by a Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear and Incomprehensible (BANI) world.

For employee’s wellbeing and performance in dynamic career contexts, Joel and Min recommend three key learnings: activate one’s motivation, take creative action and make an innovative impact.

- The third and last presentation in the conference’s first morning session was performed by Tatjana Dragovic from the University of Cambridge. Tatjana shone through the main insights from a three-year leadership development programme which aimed at translating transdisciplinary research on creativity from the fields of education, music performance, rule of law and governance into practices for leadership development in international and multicultural corporate contexts.

By engaging with music, words, and materials, participants experienced the dissolution of boundaries and silos, leading to shared possibilities and transformative experiences. The program’s arts-based approach not only provided a novel framework for leadership development but also influenced academic research by inspiring new data collection methods, such as combining visual, auditory, material, and olfactory data.

Overall, the transdisciplinary approach to translating academic research into professional practice encouraged both leaders and researchers to continually ask, “What else is possible?”.

The first day of the conference ended with Prof. Hilary Cremin’s keynote, Rewilding Education. As the title suggests, the talk encouraged educators to rethink the good life of the 21st century and what kind of education it involves.

How about you? What is a good life for you and what are the skills you need so you can have this life?

For me, one aspect of a good life is hard work and celebrating the small wins, which is what I did during the opening drinks at the end of the first day, in the company of Soila Lemmetty, my brilliant research fellow and PI of the research group JATKOT.

Tuesday, 9th of July

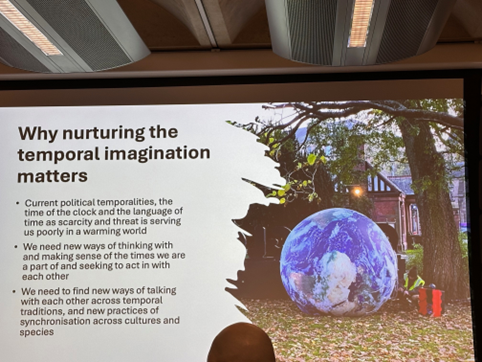

The second conference day started with Prof. Keri Facer’s keynote, Possibility and the Temporal Imagination. She discussed how time, timing, and temporal framing influence the way we think of social problems, structure solutions, and fuel conflict.

I walked away from the talk, reflecting on questions such as:

- What is time?

- How do I relate to time?

- What is a window of opportunity?

- How is the past visible in the present?

- How is the future foreseeable in the present?

After the coffee break, Carolina Cuesta-Hincapie, from Purdue University, presented in one of the parallel sessions, her work on expert perceptions on creativity in instructional design. She explored how academic experts in instructional design, with an explicit interest in creativity, perceive and define creativity, describe what creativity looks like in their profession, and identify possible challenges to include creativity in instructional design education.

One of the takeaways from this line of work is that although creativity is seen as a pedagogical tool, from the conceptual perspective, it represents a challenge to include it in their teaching.

Although creativity research has evolved over the last 50 years, creativity remains a complex concept for instructional designers to conceptualize and define. Most likely, other professions related to children and adult education face similar challenges, which is why it is beneficial to continue the conversations around creativity and learning contexts, among academics and practitioners.

Panu Forsman, from the University of Jyväskylä, argues that creative agency “entails a simple conceptualization of creativity”.

In his presentation, “Contemporary and Future Work Demands Creative Agency”, Panu proposes that supporting employees to exercise their creative agency can enable them to continuously develop their professional identity, create meaning and sensemaking, construct and distribute knowledge and respond to demands to learn and adapt to the complex reality of working life. This is another instance of research which has practical implications for organizations that desire to encourage bottom-up collaboration and innovation.

In the afternoon, Prof. Michael Hanchett Hanson discussed The Power of Creativity, in a symposium next to Prof. Samantha Copeland and Prof. Giovanni Corazza.

Michael introduced the idea of creativity as a power relationship from two perspectives:

- The local creative eco-system of the individual creator – the people in the close surroundings and the materials (places, technology, books, etc) with which the creator thinks through.

- The individual creator’s relation to the field – the larger audiences who inspire, assess, share, misunderstand and hinder the creative work.

Creative work as an exercise of power was a perspective on creativity that I hadn’t considered before. In my view, creativity is an exercise of generosity for larger audiences. Overall, The Power of Creativity symposium underlined the idea that creativity is a psychological resource in the hands of individuals with varied core values. Differently said, what do you want to create and why?

The second conference day ended with another intriguing question: What does it mean to be human in the context of life-sustaining and life-enhancing technologies? In her keynote, Society as Technology, Prof. Katina Michael, from the Arizona State University, left us thinking about an individual dilemma: will we choose the new possibilities of human-computer communication configurations without knowing fully the long-term individual and societal risks?

Wednesday, 10th of July

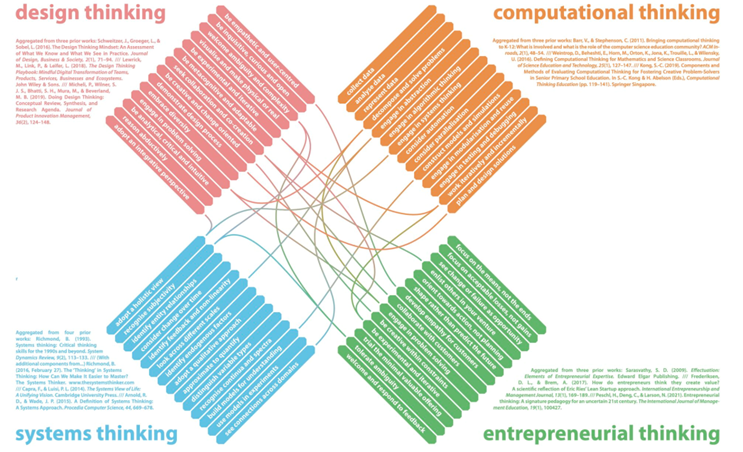

The energy of the third day of conference was set in motion by Prof. Nathan Crilly’s keynote who raised the question, “How is design thinking related to systems thinking, entrepreneurial thinking and other disciplinary perspectives like computational thinking, anthropological thinking, and mathematical thinking?”.

Such comparisons are hard to investigate because the thinking in each discipline is shaped by specific and different goals and questions. Yet, this endeavor is worth taking because it may enable deeper understanding of how the different types of thinking can be combined to address the unanswered questions in each discipline with creativity and imagination.

This kind of research sheds light on how interdisciplinary groups can become more creative as opposite to groups of individuals with the same specialization. To me, a question worth investigating is “How does creative thinking as a set of fundamental thinking skills contribute to excellence in disciplinary thinking?”.

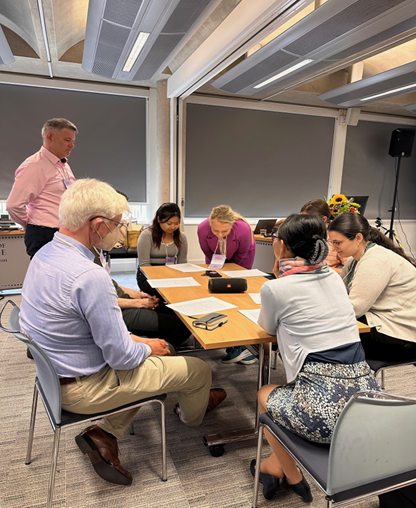

What would a possibility thinking conference be without a focus on the future shaped by AI? After the coffee break, Senior Researcher Ingunn Ness and her colleagues, Gunter Remoy, Vlad Glăveanu, and Andre Mestre, facilitated a workshop where they showcased how a pretrained AI chatbot can take the role of a creative facilitator to promote the possible in interdisciplinary groups.

The topic of discussions was, “What are the challenges and innovative opportunities of using AI to stimulate creativity in teaching and learning?”. A few volunteers from the audience gathered around a table where they answered the questions asked by the chatbot.

Moreover, since the participants were coming from diverse cultural backgrounds, they had the chance to talk in their native language and listen to the chatbot’s translation in English.

I got goose bumps as a passive participant in this workshop, feeling I am already living the future when humans form relationships with robots. For the time being, these relationships are in an early experimental phase. In the workshop, the human-chatbot interactions happened one at a time, which hampered the flow of conversation between the group members. The chatbot thus requires further training before it can act as a reliable assistant to a creative human facilitator.

At the same time, I started thinking how much human talent, money and computational resources are involved in training AI chatbots. During these heavy investments, who can take a step back and ask themselves, “What kind of jobs do we want the generative AI to do and what for? Is it for the sake of social welfare? To enhance human creativity and productivity? Or for higher profits? Who are the beneficiaries in the short and long term? How can we make it up for the losers?”.

The afternoon sessions brought another interesting question related to the role of tools in creativity and innovation: how do creative practitioners use tools to capture and develop creative ideas? Through semi-structured interviews with professionals from design, graphics, music and science, Peter Dalsgaard and his colleagues presented their findings regarding the role and nature of idea externalization in the above-mentioned creative practices.

A key consequence of this research, in my view, is that it enables understanding of the creative process stage when creative individuals are ready to share their ideas and the tools that they find relevant for their creative work.

In the context of creative thinking in design education, Dermot McInerney made a compelling case for asking questions as an essential skill for enabling understanding and knowledge construction, developing thinking, and creating meaning.

Now, take a moment to think about your profession. Suppose you wanted to raise an outsider’s interest in your domain of expertise, what would be the first question you would ask? As for design educators, Dermot’s research reminds them that it’s useful reflecting on the ratio of asking questions, telling engaging stories and active learning in the classroom.

From the skill of asking questions to that of formulating explanatory hypotheses. Thomas Ormerod reported on two studies that explored the effects of group size on collaborative problem-solving in two situations: a criminal investigative context and insight problem-solving. What would you guess? One head, two heads or three heads are better at generating alternative hypotheses? And why would it be so?

Thomas found that an individual can generate more explanatory hypotheses than two-people groups whereas three people groups generate more hypotheses than an individual. In pairs, the source of inhibition seems to stem from the differing social roles of the group members.

Indeed, this finding supports social neuroscience studies which show that the human brain is constantly comparing itself with others in social circles seeking in-group identification, which influences how the brain learns (Hobson and Inzlicht, 2016). Thus, maintaining a sense of psychological equality and belonging would create space for creativity in one-to-one conversations. The question that remains to be explored based on Thomas’ work is why do the differing social roles hamper creativity in pairs but not in larger groups of 3 or more?

Towards the end of the third conference day, the organizers and delegates gathered for the General Assembly to review the current projects and activities of the Network and open the discussion for new possibilities of collaboration. Keep an eye on next year’s conference (which will be in Dublin) to see the new projects stemming from this event. Even more, why not reach out to the conference organizers if you have an idea of involvement and contribution?

The third conference day ended with a joyful dinner, in one of Homerton College’s dining spaces.

Instead of conclusions

My participation in the conference ended on the third day. Yet, the conference continued for two more days when I would have loved to listen to the following Thursday events, at the very least:

- Jonas Bozenhard’s keynote on AI’s potential for radically new artistic and scientific possibilities.

- Lourenço MD Amador’s presentation that addressed two questions from the cognitive-linguistic perspective: what is innovation and whether innovation is a skill? I resonate with the starting argument that despite becoming more of a buzzword, the interdisciplinary conceptualizations of innovation and their relationships with related concepts like creativity have not been thoroughly investigated.

- The presentation of Soila Lemmetty and her colleagues, Ingunn Ness and Vlad Glăveanu, on the potential of employees to envision and pursue novel solutions and improvements for organizational change. The findings are intriguing from the perspective of the four types of innovation roles that employees can assume depending on the interplay between their agencies and organizational structure: visionary engines, practical advocates, evaluative ideators, and silent thinkers. This research promises powerful implications for organizations that aspire to enable bottom-up innovation.

Are you a researcher interested in creativity and possibility thinking? Or a leader interested in developing the creative potential and expertise of the people under your leadership? Which of the research ideas introduced above would you be interested in exploring further?

Last, if you prefer listening over reading, here you can listen to the podcast hosted by the vibrant professor Pamela Burnard, featuring the keynote speakers and some delegates, including myself.

Text and photos: Oana Velcu-Laitinen, postdoctoral researcher, JATKOT-research group (UEF)