The Soundscapes of Curling: From Lago Santo to the Olympics

Text & Pictures: Kaj Ahlsved

When the Someco team arrived in Cembra, we had no idea that the sport of curling was practiced at the absolute highest level there. However, already at breakfast on the first day of work, we were told that there is a modern curling hall in Cembra and that members of both Italy’s women’s and men’s national teams are currently there for training camps.

Curling is a relatively small sport in Italy, but as if to illustrate how significant the sport is in the area, the village’s own son, Amos Mosaner – Olympic gold medallist at the Beijing 2022 Olympics – happened to walk by and say hello to our informants just before we were about to start a group interview in a local restaurant. We were invited to visit Palacurling, the local curling hall in Cembra, to meet the Italian curlers and acquaint ourselves with the sounds of the hall. This was, of course, an invitation that could not be refused.

Today, curling is practiced indoors, and its sounds do not define the public sphere in the same way as, for example, football, whose soundscape practically echoes throughout Cembra when there is a match. In this sense, football is more “present” in Cembra’s soundscape, even though the sport is practiced at a very modest level in comparison with curling. In our understanding, Cembra has become something of a hub for the development of the sport in Italy.

However, just because a sport – or any other activity – is not publicly audible does not mean that its sounds are irrelevant to our project. On the contrary, in Cembra, people not only talk about the sport; there is also a unique body of knowledge concerning the soundscape of curling and the role of sound and listening in the sport.

This blog text offers an introductory reflection on Cembra’s audible history of curling, the importance of sound for the sport, and how the sport’s soundscape is constructed in broadcast. The text is informed by interviews conducted by Somecos researcher’s and Stefano Zorzanello for the Someco project and ECHOES-documentary (ECHOES 2026).

From Lochs to Lago Santo

Curling has a long and complex history and is believed to be one of the world’s oldest team sports. Paintings by a sixteenth-century Flemish artist depict a curling-like game being played on frozen ponds, but the sport is generally considered to have been further developed in Scotland, where it was also played on frozen lakes during the same period (World of Curling 2026). From Scotland, the sport spread with emigrants, particularly to Canada, where it is widely practiced today.

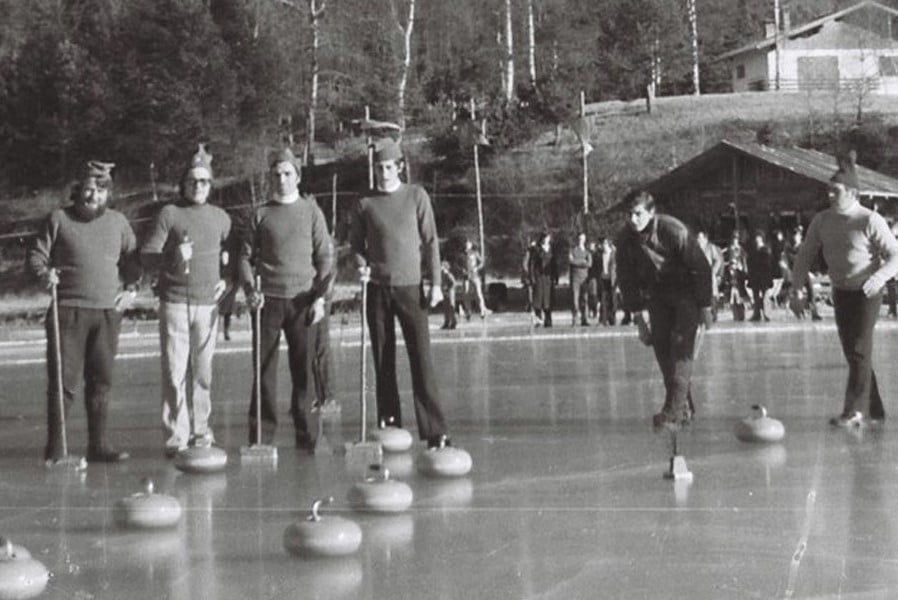

Curling arrived in Italy in the 1920s, but the first associations were founded after the Olympic Games in Cortina d’Ampezzo in 1956. At that time, curling was not an Olympic sport. Curling came to Cembra in the early 1970s, when a few young men discovered the game in Cortina d’Ampezzo and invited friends to bring curling stones to Lago Santo, a lake that was already a popular site for skating. The sport quickly gained a foothold among the local population, and a club and several teams were formed (see, for example, Donati 2022; Associazione Curling Cembra 2026; Benincasa 2023).

In the first decades, curling was played exclusively on natural ice and was completely dependent on weather conditions and temperatures at Lago Santo. Outdoors, one could hear many sounds that were not directly related to the game: cars, people talking and skating, the chirping of birds and other animals, the wind, and, of course, the cracking of the ice. The soundscape of curling was thus influenced by the surrounding sonic environment of the place where the game was played.

Players who later rose to the national level learned to interpret sounds from the ice as the conditions of the game changed through natural processes. As the lake froze, loud sounds caused by pressure changes could be heard, signalling to the players that the ice was safe to move on. The sonic environment was therefore entirely different, and most professional players today have never played the game outdoors, not even as juniors, although some fun events or bonspiels are still arranged.

When the players’ technical development began to be limited by the conditions at Lago Santo, the need for a better facility grew. Sounds irrelevant to the game were also perceived as disturbing the concentration of curlers preparing to throw and release the stone. Curlers we spoke with emphasized that silence is essential for concentration. This, together with strict safety regulations at Lago Santo that eventually prohibited play, led Cembra to build its first, more modest curling hall in 1995, followed by a modern facility with artificial ice in 2005. This marked a crucial step in the development of the sport.

After the establishment of the indoor facility, curling in Cembra progressed rapidly. From 2006 and for more than a decade thereafter, teams from Cembra – or teams including Cembra players – won all Italian championships, making the village the country’s centre of curling. The international highlight came when Amos Mosaner, together with his partner Stefania Constantini from Cortina d’Ampezzo, won gold at the 2022 Beijing Olympics – a historic result that placed both him and Cembra on the global sports map. Amos will serve as one of Italy’s four flag bearers at the Milan–Cortina Olympics in February 2026.

The soundscape of modern curling

Curling indoors on artificial ice means that everything is controlled: ice temperature, air temperature, and humidity. This controlled environment has also eliminated the environmental sounds one could hear at Lago Santo and has created the conditions for the soundscape of the modern game of curling. The technical development of the game has also been rapid, for example, the brooms previously used outdoors are of no use on pebbled artificial ice, and vice versa (cf. Schwarz 2022).

The Palacurling facility can guarantee the kind of hi-fi sonic environment (e.g. Schafer 1977) needed for, and associated with, curling in its many formats. On the other hand, this artificial “silence” reveals sounds that are the result of the machine-made conditions: a central part of the soundscape of curling is the sound of the ventilation. The machine creates a ubiquitous sound that, as one female curler highlighted, makes her feel at home:

“…if I close my eyes, I can feel the sound of this ventilation system. For me, it’s linked to the place where I grew in the sport. There is an emotional kind of link because if I think about the curling ice rink, I cannot think [of it] without this sound.”

This is a unique and interesting perspective on noise from ventilation. These kinds of noises are rarely associated with positive connotations; rather, it is typical to try to mask such sounds with music in sports environments (Ahlsved 2017) and in commercial spaces in general (Uimonen, Kilpiö & Kytö 2024). Music is generally used in curling only before the match, as part of the players’ personal routines (with headphones) or for the entertainment of the audience during intermissions or warm-ups.

The sound of ventilation is especially prominent in the clubs’ venues, such as the one in Cembra. When curling tournaments are played, for example in ice hockey stadiums or larger arenas, as will be the case at the Olympics in Cortina, one does not necessarily hear the sound of the ventilation at all.

In these competition contexts, a new element is added: the sound from the crowd, sometimes stemming from reactions to games played simultaneously on other sheets. The “silence” of the training situation is thus contrasted by elements of uncertainty that bring to mind the early days of curling, when sounds irrelevant to the game could interfere with the players’ concentration.

It is though an unwritten rule that spectators, in a manner similar to tennis, remain silent when the player is preparing to throw the stone. The sound-making of the spectators thus follows the rhythm of the game and is based on knowledge of the sport’s sound culture.

However, not all audiences possess this competence. Spectators may start clapping during the preparations, although this is unusual. If it happens, it is important that the players can shut these sounds out. As one player put it: “If I am disturbed by a sound that is outside of the sheet, outside of what I’m doing, I’m not focused enough.” The act of concentration includes a mode of focused listening that shuts out sounds not relevant to the situation or to the performance.

The soundscape of curling itself – the keynote sounds of the sport (Ahlsved 2013) – is constructed mainly by the sound of the concave granite rock sliding against the ice. Curling is sometimes nicknamed “the roaring game” due to the distinctive sound the stones make. Other characteristic sounds include the sliding noises produced by the players’ special shoes, the sounds of the brushes polishing the ice, the rocks hitting each other, and, not least, the players’ intensive communication as the stone slides toward the house. Communication, also visual, is essential and something that also needs training, especially for situations where crowd is noisy.

As the game is played on ice, a key issue for the players is to understand the ice, and how it differs from venue to venue and from sheet to sheet. Although players have other ways of measuring the speed of the rock besides the sound it makes, the sound can still provide information about both the speed and the quality of the ice.

The ice sounds different at the end of the game when it is more worn. At the beginning of the game, when the ice has more pebbles – the small “drops of ice” sprayed onto the surface by the ice maker – it has a “crispier” or more “scraping” sound. Toward the end of the game, the ice is flatter, which means more friction against the stone. This makes it slower and causes it to curl more, and the “roar” of the stone becomes slightly different. If there are problems with unevenness in the ice, it can also create a kind of “bopping” sound. In such cases, the ice needs to be fixed by the ice maker.

The sound of the brushes is also affected by the quality of the ice and by how much pressure is applied: brushing with high pressure and at high frequency creates friction and heat that melt the pebbles. This reduces friction and makes the stone slide farther or curl less (Schwarz 2022). When the ice is worn down, the sound of the broom is diminished. Sometimes the players simply and silently “clean” the ice in front of the stone to remove possible debris that could affect the curl.

The mediated soundscape of curling

Curling is an excellent TV sport, and the sport gains a lot of attention around major championships such as the Olympics. What makes it such a good TV sport is that, through different camera angles – such as overhead shots above the house and close-ups – you can follow the tactical aspects of the game on a deeper level than when watching on site.

A central part of the mediated experience of curling is that the sport’s characteristic sounds are conveyed to TV viewers through carefully planned microphone placements that capture the sounds of the game, not least the distinctive sounds described above.

In addition to microphones placed around the arena, players wear microphones so that viewers can listen in on the tactical conversations between players – conversations that would not necessarily be audible on site, where the more distant players’ voices can be drowned out by the crowd’s murmur. This can be compared, for example, to football, where players and coaches cover their mouths so that no one can even read their lips.

Being able to hear the conversation between the players adds an additional layer to the experience of the tactical game. Hearing the players discuss the play is something completely different from hearing a commentator’s voice: it places the viewer in the middle of the game, an opportunity to “be the player” (Andrews n.d.).

With this said, one can conclude that, just as in other sports (cf. Jørgensgaard Graakjær 2023 on football), the constructed and mediated soundscape of curling is composed of many sources that do not correspond to the “live” experience. For example, the sound of the stone – which travels almost 40 meters – does not convey its direction, i.e. how the stone moves away from, toward, or past a particular listening position.

Today, we hardly react to the fact that mediated soundscapes do not correspond to reality. In this sense, the sound of televised sport bears similarities to, for example, the soundtrack in movies: we allow ourselves to be fooled and immersed by the visuals and accept the sounding “illusion” of foley effects (and music) that is presented to us.

A significant difference compared to many other sports, however, is that fewer people (apart from perhaps residents of Cembra) have visited a curling rink than, for example, a football field, and therefore know what the sport sounds like “for real” or from a player’s perspective. This was also the case for us Someco researchers before we visited Cembra.

__

With this text, the Someco team wishes the entire Italian national curling team and the Cembra curling community the best of luck in the upcoming Olympic Games. Forza Azzurri!

References

Ahlsved, Kaj 2013. “Heard Any Good Games Recently? Listening to the Sportscape.” Sounding Out! http://soundstudiesblog.com/2013/11/25/listening-to-the-sportscape/ (Page read 2.2.2026)

Ahlsved, Kaj 2017. Musik och sport: En analys av musikanvändning, ljudlandskap, identitet och dramaturgi i samband med lagsportevenemang. [Music and Sport: An Analysis of Music Usage, Soundscapes, Identity, and Dramaturgy in Team Sports Events.].” PhD diss., Åbo Akademi University. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-12-3610-5

Andrews, Peregrine n.d. “Peregrine Andrews on the Sound of Sport: What is Real?” Fast and wide. http://www.fast-and-wide.com/more/wideangle/2697-the-sound-of-sport-what-is-real (Page visited 30.1.2026)

Associazione Curling Cembra 2026. “Chi Siamo” https://www.associazionecurlingcembra.it/chi-siamo (Page visited 2.2.2026)

Benincasa, Gianfranco 2023. “Quando si giocava sul Lago Santo, la storia del curling a Cembra, raccontata dall’inizio”. Rai news. https://www.rainews.it/tgr/trento/video/2023/04/curling-mondiali-ottawa-mosaner-retornaz-cembra-trentino-storia-46d4ba00-9844-45ac-b3b5-bf0ada70a86e.html (page read 3.2.2026)

Donati, Daniele 2025. “L’oro di Cembra”. Il mulo. https://www.ilmulo.it/2022/02/11/loro-di-cembra/ (Page visited 2.2.2026)

ECHOES (2026, in production). ECHOES Exploring the Contemporary Heritage of European Village Soundscapes. Documentary movie by Carlo Lo Giudice and Stefano Zorzanello.

Jørgensgaard-Graakjær, Nikolai 2023. The Sounds of Spectators at Football. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Schafer, R. Murray (1994 [1977]). The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books.

Schwarz 2022. “Why do curlers sweep?”. McGill Office for Science and Community. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/technology-you-asked/why-do-curlers-sweep (Page visited 30.1.2026)

Uimonen Heikki, Kilpiö Kaarina & Kytö Meri 2024. Background Music Cultures in Finnish Urban Life. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009374682

Word of curling 2026. “History”. https://worldcurling.org/about/history/ (Page visited 2.2.2026)