From Field to Festival: New Potatoes and Finland-Swedish Song Traditions in Nauvo

Text, pictures & lyric translations: Kaj Ahlsved

(Cover picture: Gittan Holmberg performing as Evita Päron singing unaccompanied “potato songs”. The traditional Finnish horn septet “Sointu-seitsikko” performed separately. )

The archipelago community of Nagu has a rich cultural life—among other things, several music festivals and events that enrich the everyday life and cultural experience of the permanent residents. Much of this activity takes place in the summer and is aimed at tourists and summer visitors. Among the wide range of events, there is a special festival that was held in mid-June, right at the end of our fieldwork: the Potato Festival, ”De Vita Päron” [”The White Potatoes”]. The festival is usually held the week before Midsummer, and according to informants and press texts, it has been organized in Nauvo since 2005.

Like many other towns in the Turku Archipelago region of Southwest Finland (from where about 70% of Finland’s new potatoes come), Nauvo has a strong tradition of potato cultivation. As an archipelago community, it is possible to plant and harvest new potatoes early. In short, for the non-Nordic reader: new, or early potatoes are young, freshly harvested potatoes with thin skins and a tender texture. They are sweeter and more delicate than mature “autumn” potatoes, best enjoyed soon after harvest. Often boiled or steamed, they are a seasonal summer delicacy in Finland and Sweden, not to be confused with the broader term fresh potatoes.

Nauvo was for a long time among the first in Finland to supply domestic potatoes in early summer, but even some locals now acknowledge that there are other places nearby that get there first. The number of growers has also declined over the years due to lower profitability caused by rising costs and competition from imported potatoes from especially southern Sweden. At the Festival, which mainly takes the form of a market day at the town square and the south harbour in Nauvo, visitors can buy potatoes from local producers, as well as everything from strawberries to locally produced handicrafts. A highlight is the announcement of the year’s “Potato Tuber,” (potatisknöl) a title awarded to someone who has made a significant contribution to Nauvo. This year, the title went to Raili Petra and Tero Tuomisto.

From Argentina to Nauvo

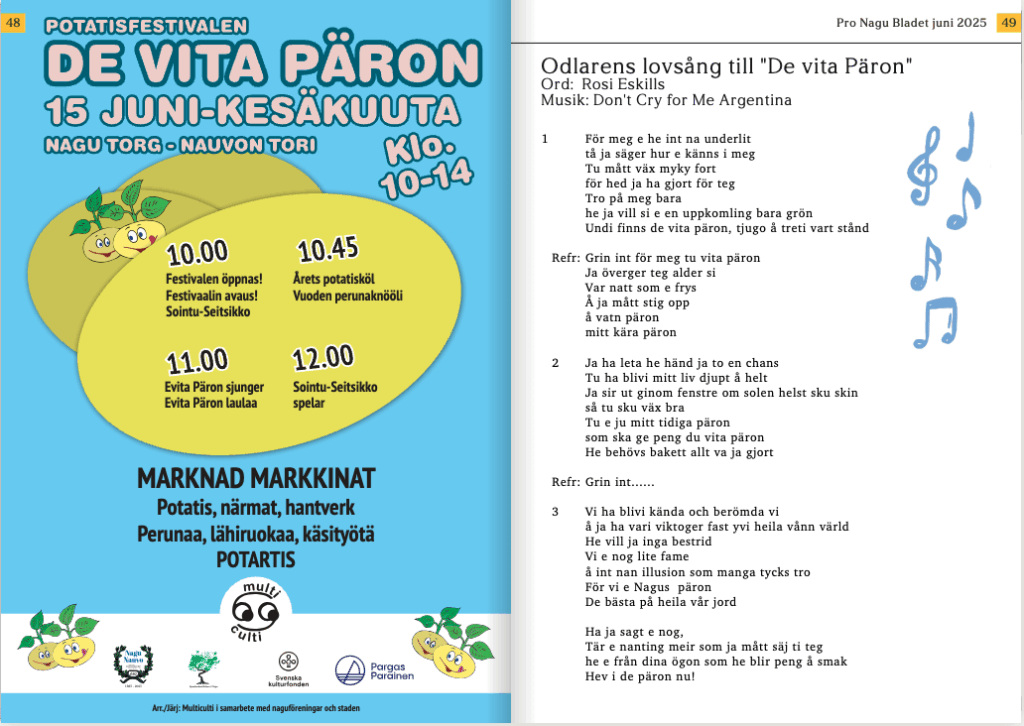

A recurring feature of the festival program has become the performance of “Potato Songs.” This tradition appears to have started back in 2005. Songs with a potato theme (sometimes humorously called “potartist”) were written by local cultural figures to be performed at the first festival. These new lyrics were set to the popular melody of Don’t Cry for Me Argentina (1976/1978). The original song was part of a musical about Evita Perón (1978) and is today perhaps best known from the 1996 film adaptation starring Madonna.

Why a song about the former president of Argentina Juan Perón’s wife, Evita, was chosen as the basis for songs about potatoes from Nagu can primarily be explained by the alliteration between “Perón” and how potato (“potatis” in Swedish) is pronounced in the local Swedish Nagu dialect: Perón – Päron (no, to be confused with pear, päärynä in Finnish). The singer of the songs therefore takes on the role of Evita Päron (Evita Potato) when performing the songs. If sung by a man, he is called Evert Päron.

At this year’s festival, Birgitta “Gittan” Holmberg, the original Evita Päron from 2005, made a well-received comeback, performing five different potato songs a cappella. The lyrics are written from both the grower’s and the potato’s perspective, focusing on the grower’s struggles but also on the potato’s (self-perceived) excellence and versatility as a food. Some songs use the entire Don’t Cry for Me-melody, while others are shorter and only based on the chorus.

New potatoes, seasonal rhythms, and food culture

In a previous blog post, I reflected on the Italian song Canta Del Mesi (“Song of the Months”) and its relationship to the changing seasonal rhythms of viticulture, since today, partly due to climate change, grapes are no longer harvested in October as they once were, and as referenced in the song. The rhythm of potato cultivation has also shifted because warmer weather now allows planting even earlier than before. Nowadays, one does not need to worry about whether there will be (domestic) new potatoes for Midsummer—they are often available for sale around the schools’ commencement weekend at the end of May or beginning of June. The peak season is around Midsummer.

An important aspect of new potatoes’ culinary and cultural history is therefore their connection to cultural rhythms, particularly the Midsummer celebration. This is reflected in the timing of the Potato Festival, held the week before Midsummer. Many buy their first new potatoes or harvest them, just in time for the festivities.

Picture: New potatoes from Nauvo were sold at the Potatofestival.

Eating new potatoes is, however, a relatively recent phenomenon in a longer historical perspective: early harvesting was once a risk. Historically, potatoes in both Sweden and Finland were a guarantee of surviving the harsh winter without “gnawing on turnips,” as the Swedish poet Dan Andersson (1888–1920) wrote in his En skön sång om potatis (“A Beautiful Song about Potatoes”) around 1900. The excellence of potatoes was highlighted here in comparison with root vegetables. Andersson even questioned what one would do with herring and snaps if one did not have “jordbär” (“earth berries”) to fill the stomach with. Andersson was referring to autumn-harvested potatoes rather than new potatoes.

New potatoes are a relatively modern delicacy associated with the Nordic summer and are often eaten in traditional ways. Krisse Bång’s potato song describes the potatoes as eaten “deeply drenched in butter, well garnished with dill,” while Kaj Nyrén writes that they should be eaten “with snaps and herring.” According to Gitta Holmberg’s own song (excerpt below), potatoes have many uses—they are eaten both at home and at restaurants, can be boiled, mashed, made into gratin, baked, or incorporated into everything from tortillas to the traditional “päronhara” (“potatorabbit”). Whatever the preparation, potatoes remain economically valuable:

Så gråt ej för mig päronbönder / Don’t cry for me potato farmers

Jag ska inte koka sönder / I will not overboil

Ni får er peng / You will get your money

Fast jag blir gratäng / Though I become gratin

Mig kan dom mosa / They can smash me

Men ni får gosa / But you can cuddle

The potato songs of Nauvo, performed at this year’s festival do not reflect climate change in their lyrics, perhaps because they were written 20 years ago when awareness of the changes was lower. The chorus of perhaps the most well-known potato song, Odlarens lovsång till “De Vita Päron” (“The Grower’s Hymn to the White Potatoes”), with lyrics by Rosi Eskills, does express weather-related challenges for the growers.

Picture: The program of the Potatofestival and the lyrics to Rosi Eskills’ potato song were published in Pro Nagu bladet’s June number 2025.

The lyrics also highlight the many obligations associated with cultivation. The original Don’t Cry for Me Argentina has been interpreted as a statement of Evita Perón’s dedication and promises to the people of Argentina. Similarly, in the verses of the “Grower’s Hymn”, the grower promises not to abandon the beloved potatoes even in the event of a night frost:

Grin int för meg tu vita päron / Don’t cry for me, you white potato

Jag överger teg alder, si / I will never leave you, see

Var natt som e frys / Every night when it freezes over

Å ja mått stig opp / And I have to get up

Å vatn päron / And water potatoes

Mitt kära päron / My beloved potato

Watering the potatoes is an effective but laborious way to prevent them from freezing and spoiling. Such weather fluctuations in Finland during the spring make potato cultivation challenging and resource-intensive. However, the changing climate, with increasing drought in southern Europe, may in the long-term increase demand for Finnish potatoes.

In summary, the songs highlight both the grower’s efforts and hopes that the potatoes will grow well and generate income. They also reflect the food culture associated with potatoes, i.e., being enjoyed with butter, dill, and snaps.

Potato songs as Finland-Swedish song culture

The earlier references to snaps and herring are interesting because they point to the social contexts of Finland-Swedish (food)culture, where both new potatoes and singing play a role—i.e., singing traditional drinking songs often combined with herring and new potatoes around Midsummer. This is especially common in the archipelago and Swedish-speaking regions of southern Finland. The writing and singing of so-called snapsvisor (drinking songs) has been seen as a typical Finland-Swedish tradition, even as part of being, or becoming, Finland-Swedish (Djupsund 2019; see also Mattsson 2002, 215). These short drinking songs are often sung at the table and are written to familiar melodies, performed without accompaniment. Sheet music is rarely needed; references to familiar melodies suffice. Knowing the melody and its original context contributes to the humour, sometimes through incongruence between text and melody. The craftsmanship of the lyricist is often judged by how well the new text fits the familiar tune, which also applies to the potato songs and humorous couplet songs in general.

Through references to drinking shots of spirits (snaps), the potato songs evoke the social situations in which traditional drinking songs are sung. The songs’ structure and humorous content also resemble the drinking songs: particularly those written only on the chorus, follow the typical snapsvisa form—a short song, often with rhyming humorous text, cleverly adapted to a familiar melody structure. “The Grower’s Hymn” even ends with a call to consume potatoes, similar to way as many drinking songs who often end with a call to drink:

Ha ja sagt e nog, / Have I said it enough

Tär e nanting meir som ja mått säg ti teg / Is there anything more I need to say to you

He e från dina ögon som he blir peng o smak / It is from your eyes that money and taste appear

Hev i de päron nu! / Dig into those potatoes now!

Nauvo is a bilingual community where Swedish dominates, though many languages, especially Finnish, are heard in summer. The fact that none of the potato songs performed were in Finnish underscores their connection to Finland-Swedish song traditions and, more broadly, Nauvo as a community with strong Finland-Swedish culture. Some songs were written in dialect, reinforcing this identity and creating boundaries between insiders and outsiders (cf. Djupsund 2019). Understanding humorous songs in dialect requires not only knowledge of the melody’s origin and history but also the ability to interpret the lyrics and their cultural meanings. In this sense, potato songs in dialect, like snapsvisor, are complex cultural products – typically Swedish – despite perhaps not being considered as a “serious” art form.

In conclusion, the songs performed publicly at the Potato Festival do more than celebrate potatoes. They also highlight—and perhaps even glorify—Nauvo’s Finland-Swedish distinctiveness, constructing Nauvo as a Finland-Swedish community deeply rooted in Finland-Swedish song as well as in food culture.

References:

Djupsund, Ros-Mari 2019. Hur härligt sången klingar. Identitet, gemenskap och utanförskap i finlandssvensk sång. Diss. Åbo: Åbo Akademi. urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-12-3885-7

Mattsson, Christina 2002. Från Helan till lilla Manasse. Stockholm: Atlantis.