Listening to the Memory on the Street

Text: Carolin Müller

Walking may be just as important to scholars of sonic environments as the sounds encountered in motion. Central to this is the relationship between the human body and the ground it touches while moving through space. Frauke Berendt (2018, 251) notes that soundwalks represent a specific form of human mobility, characterized by “a specific way of sensory attention”. This kind of mobile listening relies not only on hearing, but on a bodily attunement to space. As Mohr (2007, 188) puts it, it is a kind of “listening-based kinetic experience of the environment” — one in which the ground beneath our feet becomes an active part of sonic perception..

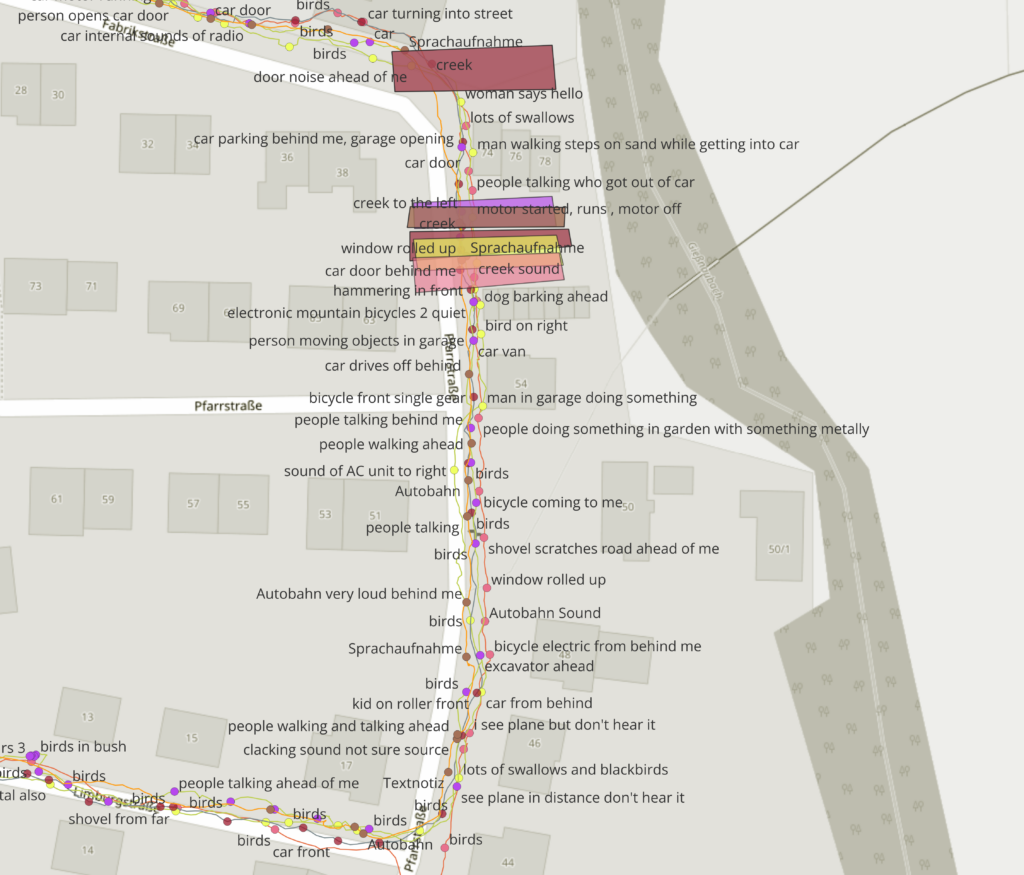

So, what cultural memory is embedded in the streets we walk, and what can listening reveal about what the pavement has to say? These questions guided our own listening walks through Bissingen’s newly paved streets, where the relationship between movement, memory, and sound unfolded in deeply local ways. One site that repeatedly emerged as significant was Pfarrstrasse—a long road on the village’s western edge, where bodies, buildings, and sounds are in constant interaction. As we moved, we became attuned not just to audible phenomena, but to the kinetic qualities of the space itself. Here, the creek doesn’t simply produce sound—it performs it, cascading along concrete, rebounding between facades, and composing a layered acoustic presence in motion. These watery rhythms merge with the footfalls of passersby, the breathing of wind through trees, and the occasional car—each sound marking a moment of contact, friction, or flow. On Pfarrstrasse, listening becomes a negotiation between movement and material; sound becomes a record of spatial tension, and walking becomes a practice of embodied attunement.

Despite assumptions based on its name, Pfarrstrasse does not derive from “Pfarrer” (priest), but from “Farrenstall”—a term used in Baden-Württemberg for a building that housed breeding bulls. These structures became widespread after a royal decree in 1882 encouraged cattle farming as a growing economic sector (Toth, Wannenwetsch, and Steigmaier 2005). By the 1960s, as cattle farming declined, many Farrenställe were repurposed into community centers—Bissingen’s included. Today, the old Farrenstall on Pfarrstrasse is home to the Musikverein and hosts weekly indoor rehearsals for the symphonic brass orchestra but also a public rehearsal in the Farrenstall’s yard once a year in Spring. The building’s location—beside the village creek, Gießnaubach—creates a unique acoustic environment. The constant splashing of the creek blends with sounds from the street and the music rehearsals, producing a layered soundscape of water and wind instruments, one tuning out the other.

During the listening walks, the creek was consistently the most prominent sound wherever it neared the road, audible throughout the day. Even as construction noises—drills, engines, and excavators—rose in volume, the creek’s sound remained steady and clear, making it the “keynote” sound (Schafer 1993) of Pfarrstrasse’s landscape. The proximity of the old Farrenstall to the creek suggests an intentional or serendipitous choice—perhaps to buffer the noise of bulls in the past, or of brass instruments today. While the original reasoning may be lost, the location continues to serve an acoustic function, absorbing and blending sounds.

One participant recalled how, during the months of the pandemic, a family closely tied to Bissingen’s church brass band took it upon themselves to perform on their veranda into Pfarrstrasse. Over the course of the lockdown, they played their brass instruments one hundred times, offering neighbors a moment of connection through sound. The street transformed into a temporary concert hall, but one marked by distance: bodies emerged from their homes to listen—scattered along the sidewalks, households standing in the then required social distance from one another. And yet, this very distance created a new kind of spatial rhythm—a choreography of stillness and spacing shaped by public health measures but animated by shared attention.

In these moments, Pfarrstrasse filled with the pulse of human-made music, a counterpoint to the eerie quiet of lockdown. The brass tones bounced off walls and mingled with the ever-present creek, layering natural and human sound into a collaborative composition. Each concert became a ritual of re-connection: the repeated gathering of bodies, the regularity of sound, and the way listeners reinhabited the street as a shared auditory space—all combined to inscribe this period into the village’s collective memory. The collective act of listening in the street, though physically distanced, became a form of communal movement—a kinetic rhythm of resilience against solitude.

The narratives and sonic markers of Pfarrstrasse reveal it as a repository of acoustic memory in Bissingen. These memories stretch across generations and illustrate how people have continuously organized themselves in relation to the sounds of their natural and agricultural surroundings. As a site of music-making and mingling sounds, Pfarrstrasse remains in flux—an acoustic space shaped not only by what is heard, but also by how it is moved through. This interplay came into sharp focus during the pandemic and now newly settled families bring new sounds of children’s voices and the sound of dogs to the neighborhood. Pfarrstrasse, then, is more than a setting for sound; it is a living archive of kinetic memory, where walking, listening, and gathering continue to shape how sonic environments are felt, remembered, and inhabited.

Works Cited:

Behrendt, Frauke. 2018. “Soundwalking.” In The Routledge Companion to Sound Studies, 249–57. Milton Park, Abingdon ; New York: Routledge.

Mohr, Hope. 2007. “Listening and Moving in the Urban Environment.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 17 (2): 185–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/07407700701387325.

Schafer, R. Murray. 1993. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Simon and Schuster.

Toth, Josef, Wannenwetsch, and Karlheinz Steigmaier. 2005. Band 9 – 2002 – Museum Farrenstall.Pdf. Edited by Museum am Widumhof/Museum Farrenstall. 350th ed. Vol. 9. Urbach: Druckerein Roth. https://www.urbach.de/site/Urbach-2023/get/params_E825428422/23491978/Band%209%20-%202002%20-%20Museum%20Farrenstall.pdf.