The historical and current issues at stake during COVID-19 epidemic in Brazil

By Mariana G. Lyra

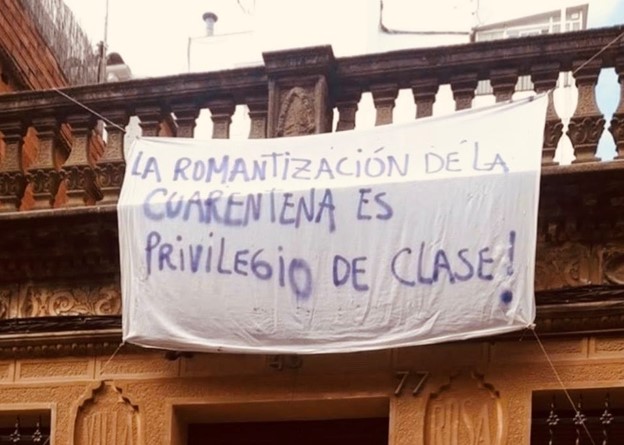

“The romanticism of the quarantine is a class privilege!” Photo source: unknown from the Internet

Brazilians are fighting COVID-19 by facing current and historical issues. The numbers of registered cases and deaths are not so high, compared to the world ranking or considering that Brazil has a population of more than 220 million inhabitants. At the moment I am writing this piece, there are 2,024,675 COVI-19 cases around the globe, 615,406 only in the United States, followed by Spain with 177,633 cases. Brazil appears on the 14th place, with 25,758 people infected. The devil, however, is in the details.

The Washington Post editorial from the 13th of April is emblematic: Brazil currently has the worst leader in the world to deal with the pandemic. According to the editorial, Mr. Bolsonaro is putting the Brazilian population at risk by having a recurrent discourse that is, at the same time, minimizing the effects associated with the pandemic and misleading how Brazilians should prevent contamination. Critics on how the Brazilian president is dealing with the COVID-19 situation have been signaled before by The Guardian editorial, remembering that Facebook and Twitter have deleted Bolsonaro’s posts about the pandemic due to its harm to the overall users. The posts were about unproven remedies and attacking the practice of physical distancing. The NGO Human Rights Watch considered that Bolsonaro is sabotaging the Health Ministry and the Governors’ regional efforts to manage the pandemic, putting the Brazilian at grave risk.

The historical context of social inequality in Brazil, also reflected in other Latin American countries, deepens the risk. For example, in times of remote learning and access to information, 42% of the households in Brazil have no computers. Almost half of the population has no access to proper sanitation or water. More than 10% of the population is unemployed and 38.4 million Brazilians have an ‘informal’ job, the ones which are the first to face the economic consequences of the pandemic.

Adding to this context, while the USA and Europe are fighting with each other to buy more and more health supplies and equipment such as masks and breathers, poorer countries in Latin America and Africa are left out queuing for a few months to get those items. In Brazil, it has been hard to grasp the real dimension of the problem due to the lack of tests. Brazil is testing 296 people per million inhabitants, while the USA is testing 8 866 people per million. In other words, the actual numbers in terms of infected people would be up to 15 times bigger than the official ones, and projections are estimating Brazil to be the second most infected country in the world, behind the USA.

The exponential rise of infected people in Italy, Spain, and the USA teach other countries how fast health systems can collapse. Brazil has in average one hospital bed per 10 000 inhabitants in the public system. The lesson from Italy and China indicates the need for 2.4 hospital beds per 10 000 people in the epidemic peak, more than double of the Brazilian capacity. With cuts on the annual budget, the health system in Brazil has a perilous capacity to deal with COVID-19, and units are lacking equipment, supplies, and even soap and water in some cases.

Without top-down clear directives, the citizens are self-educating themselves on how to fight the pandemic and organizing independent initiatives to help marginalized communities. Groups are providing water bottles and liquid soap to the most vulnerable ones, such as homeless and regions of big cities with a notorious incidence of drug trafficking and drug use in public. The following weeks will reveal progressively how severe the situation in Brazil is. Most likely the future will repeat the lyrics of that Chico Buarque’s old song – another unfortunate page of our history.

Mariana Lyra is an environmental policy researcher and doctoral student at the University of Eastern Finland. Her main research interests are extractive industries, local conflicts, and social movements. In particular, she is interested in shedding light on the groups fighting for social and environmental justice.